Rediscovering a Lost World

-

The City of Ipoh, in the Malaysian state of Perak, is the country’s third-largest city.

-

Established in the 1880s, Ipoh maintains a connection with its colonial roots through the preservation of the old buildings from that era.

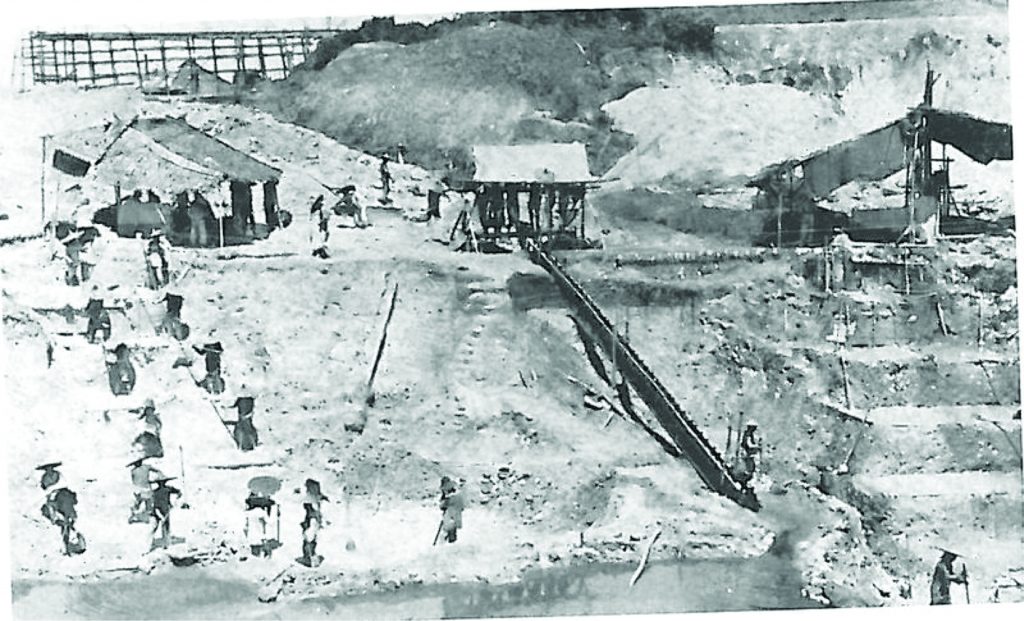

Like many Southeast Asian cities that grew into prominence in the 20th century, Ipoh owes a lot of its growth to industrialization. In particular, the second tin rush in the 1920s and 1930s helped turn Ipoh into the “City of Tin” and an important economical hub — paving the way for its expansion and modernisation.

The tin mining industry did a great deal of damage to the area during its heyday.

The theme park, built on formerly mined out land that became a tourist destination, allows visitors to appreciate a number of natural formations – including limestone hills that are millions of years old, and a geyser that shoots hot water up to 40 feet (12 meters) into the air.

What has arisen from the former tin mines is a sprawling modern property and theme park that was built while preserving the surrounding natural environment.

The natural hot springs, which pump about 300 million litres of water per day at 70 degrees Celsius (158 degrees Fahrenheit), are another big attraction for tourists.

Appreciating history

The Lost World of Tambun is a tribute to both the industrial and environmental history of Ipoh.

While its status as a tin-mining center may now be in the past, Ipoh continues to thrive through another industry: tourism. It’s become a hotbed for tourists who want to experience a glimpse of Malaysia’s history, delicious local delicacies such as their famed Ipoh Hor Fun, Nasi Ayam Taugeh, Mee Curry, all within the Lost World of Tambun, a family holiday destination.

The area also houses a “Tin Valley” that teaches tourists about the city’s tin mining roots. It shows an appreciation for the industry that helped modernize Ipoh and provides youngsters with an enjoyable hands-on experience that simulates the tin ore panning experience.

The “Dulang Washing” area in the Tin Valley simulates what the tin panning experience was like during the tin boom.

It pays testament to local culture by ensuring that visitors learn about the myths and folklore that was revered by the region’s ancient inhabitants.

One of these ancient sites is the Gua Datok Cave, situated inside a 400 million-year-old limestone hill. People have been praying in the cave for many years and it is considered a sacred site. It’s a huge area with three chambers – and can fit a plane inside.

The 400 million-year-old Gua Datok Cave is a sacred place for many locals, who have prayed there for countless years.

There are plenty of other attractions as well. Visitors can choose to explore the Night Park or Water Park, they can also go to the adventure park and take part in a number of physical activities such as cave exploration, and even glamping.

Responsible tourism

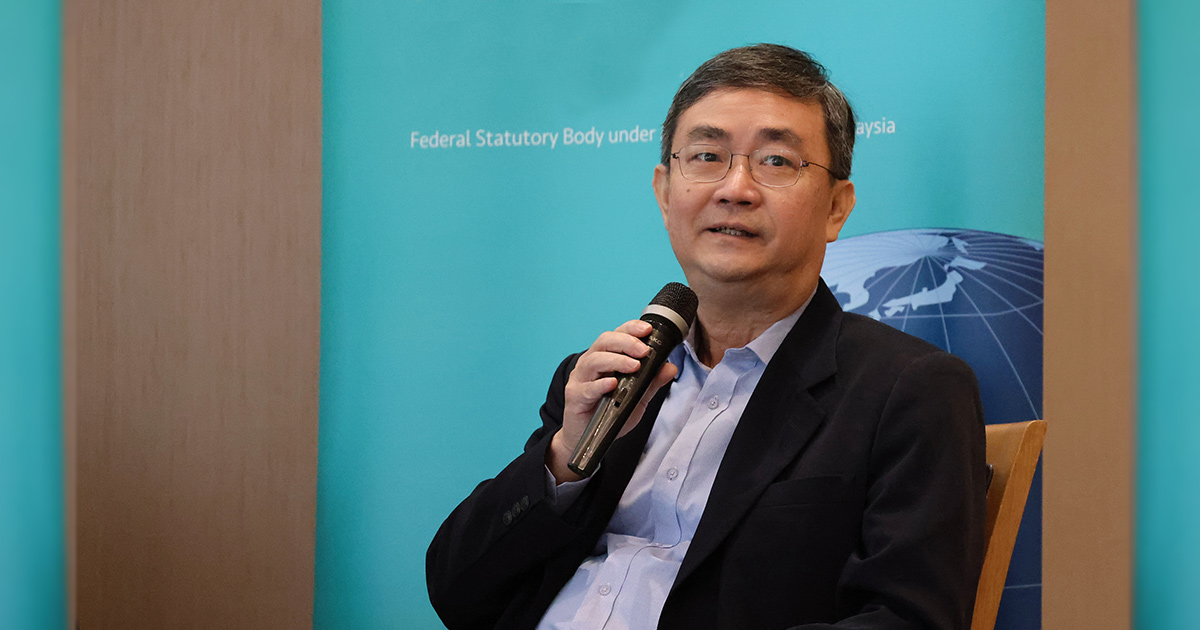

Though tin mining may have helped build the foundation of modern Ipoh, some have turned their focus into building for the future while keeping the natural environment in mind. One of these individuals is Tan Sri Dr. Jeffrey Cheah AO, founder and Chairman of Sunway Group – who has a knack for turning wastelands into wonderlands.

Sunway City Ipoh is an example of Cheah’s strong belief in developing properties with a sustainable infrastructure. Born and raised in the small town of Pusing, which is also in Perak, Cheah has many fond memories of enjoying Ipoh’s natural wonders during his youth. These memories served as an inspiration to build something that future generations would appreciate.

When he first purchased the land, Cheah discovered that a large part of it had already been mined out by tin mining. Fortunately, swaths of nature — including hot springs, the jungle, and the hills — still remained. It reminded him of his youth when he would come to the area to boil eggs, just as the late Sultan of Perak also used to do. The area held something special for Cheah, and he wanted to build something exciting around it. He certainly managed to prove his vision, as evidenced by Sunway City Ipoh being a five-time winner of Fiabci awards, including being the World Gold Winner in the Resort Category of the 2015 Fiabci Prix d’Excellence.

Eventually, he built a sprawling township, which spans 1,300 acres (5.2 square kilometres) and includes both residential and commercial facilities. It also houses The Lost World of Tambun, an eco-friendly theme park and hotel that is one of Ipoh’s most popular tourist destinations.

The area’s development followed a strict policy that centered around preserving Ipoh’s natural wonders, like the ancient limestone hills and surrounding vegetation.

All of the park’s rides and attractions are built without cutting down any of the trees. Should there be a dire necessity for this vegetation to be removed, it is relocated to other parts of the park instead of being cut down.

Ensuring sustainability through technology

Environmental protection through technology is also an important part of this development policy. For example, The Lost World Hotel encourages the charging and use of electric vehicles (EVs) by providing two charging lots for drivers. The property has also worked toward minimizing the usage of its diesel trains.

Additionally, The Lost World Hotel uses an inverter air conditioning system that doesn’t use ozone depleting-substances compared to older systems.

Water wastage is kept to a minimum in The Lost World of Tambun and Sunway City Ipoh. Excess hot springs water is channelled into their water park, and water from the natural streams and lakes is re-used for irrigation. This water is treated with mineral bio blocks. Effective microorganisms are also used to clean their animal enclosures.

There are many people from around the world who want to stay at hotels and properties that preserve their surrounding natural environments – and they are willing to spend extra money to support these projects. These high-value tourists will play a key role in driving Malaysia’s tourism revenue for the foreseeable future.

This has been an affirmation for forward thinking organizations like Sunway Group, who have been building sustainable properties for many years.

Building for future generations

Sunway Group’s efforts are driven by a sombre understanding from its founder.

He believes that climate change is real. If we don’t take steps to address it now, then everyone will have problems in the future.

He hopes that his efforts can inspire other companies and individuals to fight climate change and the destruction of the environment.

The article originally appeared in National Geographic.